In his fascinating book, The Wood Age: How One Material Shaped the Whole of Human History (HarperCollins, 2021), Professor of Biological Sciences Roland Ennos, referring to a relatively obscure but potentially critical historical incident, makes the following statement: ‘Wide plank floorboards became highly fashionable as a mark of an independent spirit’.

As creators of fine wood floors, and with over a hundred wide, extra-wide and superwide floors in our collection, we simply had to share this story with you.

The Royal Navy

In the early 16th century, Henry VIII became the first English monarch to establish a standing Navy. His daughter, Elizabeth I, affirmed and fortified the nation’s maritime dominance with the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588. This dominance was challenged during the following century by the Dutch Republic, supported by its formidable merchant fleet and the deep pockets of the Dutch East India Company. Despite this, the British Navy continued to defend and further the nation’s interests and ambitions with decisive victories at the likes of the Battle of the Gabbard (1653), the Battle of Lowestoft (1665), and the St. James’s Day Battle (1666).

By the end of the 17th century, however, the British Navy was beginning to feel the strain, particularly following their defeat at the Battle of Beachy Head (1690), this time at the hands of the French. A significant contributing factor to the difficulties experienced at this time was the shortage of trees tall and broad enough for mast-building in Britain. The nearest source for mast timbers was in the Baltic, but this region was also exploited by the French, Spanish and Dutch.

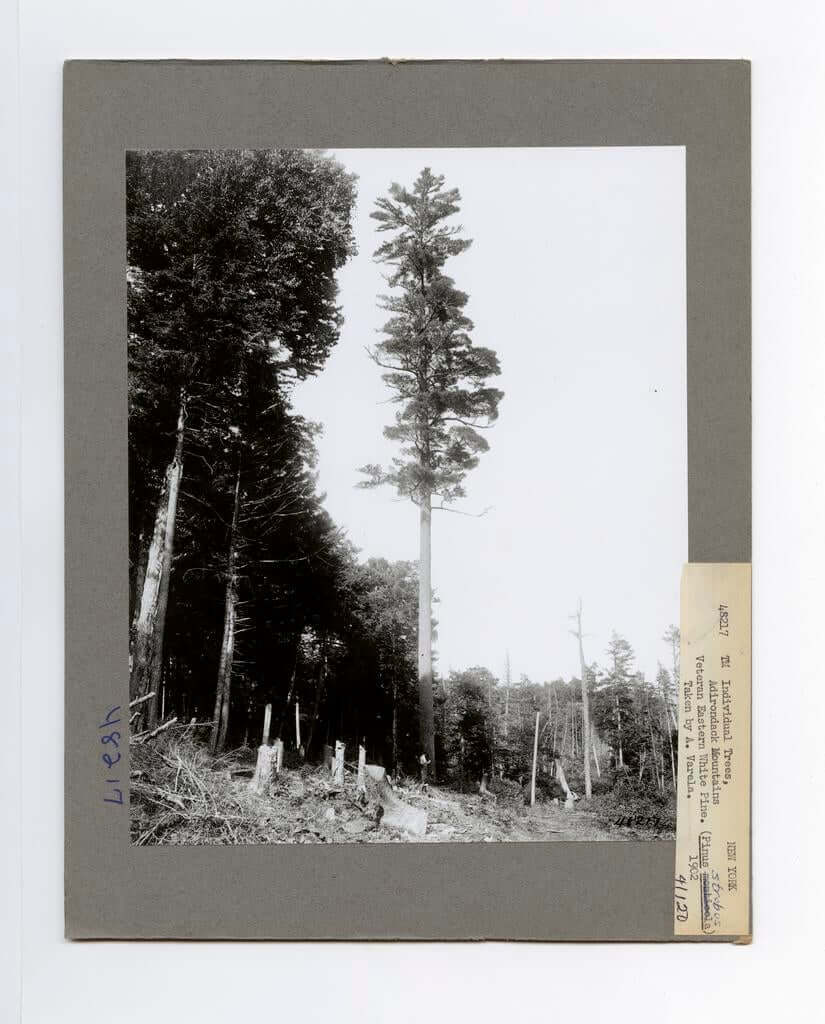

Eastern White Pine

Fortunately, Britain’s New England colonies across the Atlantic boasted healthy populations of Eastern White Pine (Pinus strobus). Generally recognised as the tallest tree in eastern North America (though challenged by the deciduous tulip tree), the Eastern White Pine can typically grow up to a height of over 150 feet, with a common diameter of approximately 3 feet. This made it the perfect specimen for mast-making. In fact, during the 17th and 18th centuries, tall pines generally became known as ‘mast pines’.

Largely for the same reason the lumber of the Eastern White Pine was perfect for mast-making, it was very popular for a range of other applications, and a lucrative component of the American lumber industry. In his History of the Lumber and Forest Industry of the Northwest, George W. Hotchkiss says of its wood: “Being of a soft texture and easily worked, taking paint better than almost any other variety of wood, it has been found adaptable to all the uses demanded in the building art, from the manufacture of packing cases to the bearing timber and finer finish of a dwelling”. And naturalist, essayist, poet, and philosopher Henry David Thoreau (1817–1862) remarked, “There is no finer tree”.

The Broad Arrow

In 1708, the New Hampshire General Court passed an act reserving all trees in the province suitable for mast-building for use exclusively by the British Royal Navy, reflecting a 1691 law passed in England reserving all trees with a diameter of more than two feet. In 1722, the law was amended to reserve trees with a diameter of just one foot. ‘Surveyors of the King’s Woods’ stamped these ‘reserved’ trees with the ‘broad arrow’ marking them as property of the Crown.

Simmering Unrest

This was deeply unpopular, particularly as the Crown set the prices for this mast wood, making it far less profitable for American lumber traders. As with all edicts dispatched from three-and-half-thousand miles away, it was ignored by many, and Eastern White Pine continued to be used in the construction of Colonial homesteads. It’s width, made it particularly effective for the creation of floorboards. Wide planks appealed for the same aesthetic reasons they do today—they create a sense of space and luxury, and allow the wood’s character to shine—but in the America of the 1700s they also represented the burgeoning sense of independence that was growing at the time, an anti-autocratic streak of self-determinism.

In 1734, the Lieutenant Governor of the Province of New Hampshire, David Dunbar, while investigating misappropriation of the Crown’s mast pines, was, along with ten of his men, assaulted and driven from Exeter, New Hampshire, at gunpoint, in what became known as the ‘Mast Riot’. This is considered to be one of the earliest skirmishes between representatives of the monarch and American colonists.

Tensions Rise

In March 1765, in an effort to tackle the debt accumulated during the Seven Years’ War with France, the British introduced the Stamp Act, which imposed a tax on a range of printed materials, including wills, deeds and playing cards. Riots broke out in Boston, then in various seaports, and Parliament was forced to repeal the act.

Two years later, in an effort to reassert their authority, Parliament passed the Townshend Acts, taxing British exports such as glass, lead, paint, paper and tea. Inspired by a covert group of colonial business leaders, The Sons of Liberty, New England merchants boycotted all but the most essential goods. The impact of this action was so profound that, in 1769 in excess of 2,000 thousand British soldiers were sent to Boston to restore discipline and respect for the Crown. Not only did this attempt to regain authority fail, it ultimately resulted in the Boston Massacre (1770), the precursor to a key milestone on the path to the American War of Independence, the Boston Tea Party (1773).

However, sitting not insignificantly between Massacre and Party, is little spoken-of event, The Pine Tree Riot.

The Pine Tree Riot

On 7h February 1772, John Sherman, Deputy Surveyor of New Hampshire, discovered several mills in Hillsborough County disregarding the 1708 act. Some of the accused agreed to pay a fine, others refused. A few weeks later, a warrant was issued for the arrest of the delightfully named Ebenezer Mudgett, identified as the de facto leader of the rebels. The Sheriff and Deputy of Hillsborough County, Benjamin Whiting and John Quigley, were sent to the town of Weare to enforce the warrant.

Things did not go smoothly. Mudgett led between 20 and 40 men (accounts vary) to the Pine Inn, where Whiting and Quigley slept. The sheriff and his deputy were beaten with switches and driven from the town through a gauntlet of taunting townsfolk.

A posse of soldiers was sent to deal with this act of sedition and rounded up the perpetrators. They were charged and found guilty of rioting, disturbing the peace and assault. However, none of the guilty were imprisoned, instead being levied a fine of 20 shillings each and the cost of the hearing.

The penalty was considered slight and demonstrated the Crown could be effectively resisted, and some believe this directly inspired the Boston Tea Party, itself seen as the moment the fuse of the American War of Independence was lit.

“…a Mark of an Independent Spirit.”

It’s quite a leap from wide plank flooring to July 4th fireworks, but those colonial homesteaders with their broad Eastern White Pine floorboards doubtless felt they were doing their part in advancing the rights and freedoms of their more radical kinsfolk. And as you peruse our collection of wide planks, you might look at the likes of Abbot, Cassava and Tattenhall a little differently from now on.